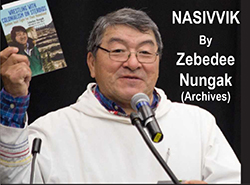

NASIVVIK By Zebedee Nungak,

Windspeaker Columnist; Archives 2006

Nasivvik is an Inuktitut word that means vantage point. It can be a height of land, a hummock of ice, or any place of elevation that affords observers a clear view of their surroundings to make good observations.

By the time we read these words, another federal election will have been wrapped up, and we will have counted the number of Aboriginal people elected as MPs on the fingers of one hand.

This election's results should unite the Indian, Inuit and Métis people of Canada in one great drive to persuade this particular Parliament to tackle a major reform in its make-up: That of getting the nation's Aboriginal peoples properly represented in Parliament.

The concept of Aboriginal MPs more numerous than the digits of one hand is in a strange place in the nation's political timeline. If left to the natural process of political evolution, it could well take another 100 years for Aboriginal population levels to cross the thresholds required of it by present electoral laws for Aboriginal people to attain a real presence in the national legislature.

Sparking a More-Aboriginals-in-Parliament revolution is highly unlikely. Imagine convulsing Parliament sufficiently to do something greatly un-natural to itself: Willingly making room for the original inhabitants of the lands "discovered" and "settled" by immigrants from other lands. With such a revolution a non-starter, other ways to get the desired result with minimal agony have to be explored, discovered, and implemented into reality.

When the government of Canada started a program of funding Indian, Métis, and Inuit organizations in the 1970s, a new dynamic was initiated. Native people, as they were then called, started making direct and frequent presentations of their communities' and peoples' needs to various organs of government. Out of these interactions, a new relationship was forged.

This relationship, though, was a lop-sided one. It could be summed up in the phrase "Fund us so we can lobby you for benefits for our people." Nevertheless, one of the new dynamic's by-products was a generation of Aboriginal representatives quickly acquiring expertise in "lobbying."

Parliamentary committee rooms became as familiar as walrus-hunting grounds for Inuit political operatives engaged in another level of "hunting" for programs that other Canadians took for granted. Many an appointment with a minister was "harpooned," and pulled in for all it was worth in pursuit of favorable consideration for benefits in housing, education, health or transportation subsidies.

A lot of dignified begging was done. The country's political masters were met more than half way as Inuit operatives did this in English as a second language. Inuktitut hardly ever jarred the ears of the government bosses on whose turf most meetings happened in.

Furthermore, the framework in which all this was taking place was a Benefactor/Beneficiary relationship, fraught by its very nature with inherent uncertainties and traps. Variables included things such as: Which party is in power? What are their policies? Who is the minister of Indian Affairs? Who is the prime minister? Do any of these factors positively favor the issue at hand?

Eventually, processes to negotiate land claims were instituted, and Inuit in four distinct regions of the country signed agreements with governments of the land, which, in the minds of those who governed the country, settled these constituencies' niches in the country's political structure.

However, a closer look at this patchwork quilt of land claims agreements will reveal that they are based on a legal imperative imposed by the governments: The surrender and extinguishment of Aboriginal rights and title to the lands in question, in exchange for enumerated sets of rights.

Their respective negotiation durations also reveal an incongruous asymmetry, which should have attracted righteous attention in Parliament. The James Bay Agreement was finalized in two years; the Inuvialuit Agreement in eight years; the Nunavut Final Agreement in 17 years; and the Nunatsiavut (Labrador) Agreement in 27 years.

Governments did not have a battery of Inuit Members of Parliament breathing down their necks asking questions like: "Who else in this country is forced to agree to such pre-conditions, simply to have their rightful place in Canada acknowledged and respected?"

"What on Earth is taking so long?" (In the case of Labrador) "Why is duress being applied here? (In the case of Nunavik)

All this is to say that Canada's Aboriginal people should get collectively determined to get out of the dignified begging business. Their leaders should drive hard for electoral reform, and cause Parliament to accommodate 20 to 25 Aboriginal seats in Parliament.

They would then straighten out the federal government's tendency to design "one size fits all" policies for Indian, Inuit, and Métis, each of whose distinctness deserves tailor-made accommodations from government. Mind you, there will be occasions for "pan-Aboriginality" for some major issues. But these would be determined by Aboriginal MPs' realistic assessments of their collective interests, and not by others.

Assembly of First Nations National Chief Phil Fontaine could then appear, post-electoral reform, with Canada's Chief Electoral Officer Jean-Pierre Kingsley, encouraging Aboriginal voters to vote in federal elections!