Image Caption

Windspeaker.com Books Feature Writer

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

As wildfires force First Nations communities to evacuate in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, the easiest way for allies to step up is to donate to the Canadian Red Cross, says Rose LeMay, author of Ally is a Verb: A Guide to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.

But allies can do even more. As accommodations in hotels become increasingly strained, LeMay says allies can call for universities and colleges to open up their student housing.

And allies can lobby politicians for stronger, faster responses.

“I don't think there's anything wrong at all with lobbying for effective government services. I'm guessing governments from provincial, territorial to federal governments, are overwhelmed. It seems that they are doing as best as they can,” said LeMay.

“Governments probably needed to be thinking about (wildfires) a year ago. I question why they haven't built up their emergency response, but if we nationalize anything in this era of Canada Strong, how will we nationalize wildfire response? Because the lack of coordination between provinces and the federal government is glaring. Let's take that step.”

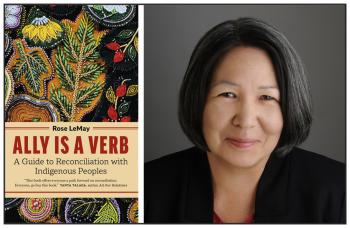

LeMay, who is a speaker, trainer and coach on reconciliation, has put her training work into her debut guidebook Ally is a Verb to help the “next-level ally for reconciliation…This book is for non-Indigenous allies who already know they want to do something but are not sure about the next steps.”

For more than 20 years, LeMay, from Taku River Tlinglit First Nation in northern British Columbia, has been training Canadians in reconciliation, with most of her work sector specific. While she used that training content in her book, she admits it was a challenge to stay more generic.

“I found it actually quite difficult to write a book knowing that I couldn't respond to questions. I felt a lot of pressure to get it as close to good as possible because I don't have a do-over. It took me a lot more time for sure,” she said.

In Ally is a Verb, LeMay writes, “…I had a theory that non-Indigenous Canadians would care about reconciliation if they only knew about the history and racism, if they only knew about the problem that reconciliation would solve.”

She dives into the “foundation of the Great Canadian Lie—because the rhetoric and the legal doctrine were instruments for getting the land and natural resources away from the Indians.” She outlines the history of Indigenous people in Canada.

LeMay moves on to talk about the work undertaken by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Indian residential schools and the lack of movement by the federal government on the TRC’s 94 Calls to Action released in 2015.

On May 27, 2021, she writes, when 215 unmarked graves were identified at Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc at the site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School, the Great Canadian Lie died, and the Canadian flag flew half-mast.

Lemay believes that Canadians don’t need governments to guide them to do the right thing.

“It might be a bit idealistic, but that's what change is. Change is talking about a future which we haven't achieved yet,” said LeMay. “Change doesn't happen in secret and it doesn't happen slowly… And it needs to be (said) out loud.”

LeMay delivers change through a change management approach, which names the problem and the solution then encourages people to be part of the solution.

Right now, she says, none of the levels of government are stepping up to make the changes.

“There's always been this sense that somebody else will do it. Well, nobody else is doing it. The federal government isn’t doing it. Provincial, territorial governments are inconsistent depending on the party they elect. But societal change actually is local. It starts with us. Canada is a fairly small country. We affect change to the people we know, so we all can start,” said LeMay.

There is no time to “slow-walk” reconciliation, she adds, and “perfection is completely overrated.”

“Our kids, our grandkids, deserve us to do what we can in our work lives, not wait for somebody else to do it,” said LeMay.

Throughout her book, LeMay offers ways and resources for allies to acquire more knowledge, and exercises to become actively engaged. Some of that action will bring about unavoidable discomfort, she says.

“It is easier to say nothing in the face of racism against an Indigenous individual, but the regret of doing nothing may sting for a much longer time than the discomfort of standing up,” she writes.

For people who aren’t yet ready to be allies, LeMay says this: “I wouldn't want, and this is what I tell clients and corporations, you do not want to be the last one in your sector to get on this reconciliation because we'll call you out.”

Ally is a Verb: A Guide to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, published by Page Two, is available at amazon.ca.