Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

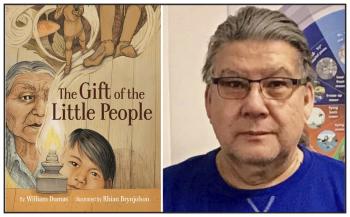

In the work The Gift of the Little People by storyteller William Dumas, Kākakiw navigates a deadly virus that is decimating a local population, working with “small beings who are just like us”.

Dumas describes his book as a “reclamation of Rocky Cree culture” with a story that looks at “why we were well”, and how that wellness translates into today's society.

The Gift of the Little People hit shelves in February. It is part of the Six Seasons of the Asiniskaw Īthiniwak storytelling project published by HighWater Press. The project also will feature Dumas’ upcoming book Amo's Sapotawan, set for release this fall. Previously, Dumas authored Pisim Finds Her Miskanaw, which was released in 2020.

Dumas was born in South Indian Lake, Man. He has worked for nearly three decades as an educator and said that extensive dialogue with people who know has helped solidify his belief in the existence of the Little People, which in turn helped inspire his recent work.

“I've been doing this research for years, and the past few years have been amazing. You wouldn't believe the stories that have been shared with people (that) have actual sightings of the Little People to this day,” Dumas said.

“So we have a lot of confirmation from a lot of other people that say ‘yes, they still do exist. They're still around’. I can't say for sure I've seen them, but the reality is the stories that are being shared with me by my relatives and friends. I believe them because I don't think people make up the stories when they see these Little People.”

Dumas understands the parallels between his work and the COVID-19 pandemic, but wants readers to ultimately take away a positive message.

“When we watch the news, there's a lot of trouble out there in the world. What the book talks about, in the end, is about hope,” Dumas said. “There is always hope, no matter what happens to human beings.”

Dumas said the connections between the book and the pandemic were mostly coincidental, though, admittedly it was a “perfect time for this story to come out.”

“It wasn't really planned,” Dumas added. “It just happened like that.”

Dumas recalls a conversation he had with friends around a campfire ‘years ago’ about the importance of preserving the Rocky Cree language in his stories.

“We were talking about how the language is so crucial to keeping our culture alive,” Dumas said. “The language is very crucial.”

The book’s target audience is children in the fourth to sixth grades, typically ages between nine and 11 years old. But Dumas said his previous work for children has often resonated with adult populations as well, and mentioned an interaction he’d had with an adult man who’d read his work several times over.

“This information, he never got it from his parents,” Dumas said. “It's not only children that are interested in looking at the history of their relatives of the past.”

Dumas said they have developed the book into an educational tool with a teachers’ guide.

"We are getting really positive feedback from the teachers who are working with the kids in the classrooms,” he said.

While Dumas is the author on the book’s cover, he gave credit to the team that helped see it through the development process.

“I consult a lot with knowledge keepers that are still fluent in the language or that have a background in that time, in that time period. So I consult a lot with them, what was going on and then we take that information to the academics, and we start putting it together,” Dumas said. “It's just an amazing way of doing a story.”

Warren Cariou, a University of Manitoba English professor, was one of the people tasked with helping Dumas with the book’s production.

“A lot of the work that I do with oral traditions is thinking about the ways in which oral stories can be adapted into written form,” Cariou said. “I’m just trying to make it sound like the oral story, but to make the work within the conventions of fiction. That was sort of my role.”

Cariou said one of his key responsibilities was writing out a written version of Dumas’ oral stories while looking to make sure there weren’t any discrepancies between the two versions.

“That means a lot of going back and forth [with the author],” he said.

And like the children in the classroom or the adults who may be reading Dumas’ work, Cariou felt enriched by the work.

“It’s an incredible learning experience for us,” Cariou added. “And we're learning about not just how the stories go but also about doing our scholarship differently, and recognizing [how to navigate] community-based work like this. We just learned so much.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.