Image Caption

Windspeaker.com Books Feature Writer

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

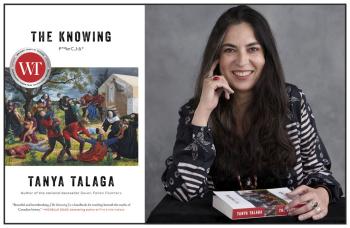

It’s a “special honour,” says award-winning journalist and author Tanya Talaga. Her newest non-fiction book The Knowing is being taught in Grade 11 at the Toronto District School Board, one of the largest school districts in Canada.

“Considering (Toronto) is Annie's final resting place. She started off at Fort Albany almost 3,000 kilometers north, and here she lay for all these years, unseen, in an unmarked grave, and the fact that her story will be taught to the next generation is pretty awesome to me,” said Talaga, who is of Anishinaabe and Polish descent and a member of the Fort William First Nation.

But The Knowing, recently shortlisted for the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing, is much, much more than Talaga’s painstaking years-long journey to find where her great-great-grandmother Annie Carpenter was buried.

“I never thought I would rewrite the story of Canada, which is what I partially do in the book,” Talaga said.

Talaga continued the search for Annie after the passing of her Great Uncle Hank Bowen. Bowen had spent decades on the quest that “consumed him,” writes Talaga. When her mother gave her Hank’s “brown collapsible file folder stuffed with papers, maps, letters and notes,” Talaga took up the mantle.

She deftly braids her personal and heartbreaking family story of colonization, residential schools, health institutions, and violence with the broader story of First Nations people.

“All of us as First Nations people were wanting to find the people that we lost and those that are just gone. And for me as a journalist, it's what I have been doing. I find people. I find their stories. I've been doing that for over two-and-a-half decades,” Talaga said. “I feel like my mom gave me my greatest assignment.”

Talaga had two Bristol boards covered with pieces of paper. One board was a historical timeline that began in 1678 with the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Albany, and the other was a board containing her giant family tree. As she found information, she stuck it to the relevant board.

Talaga made use of one volume (contained in two books) of the detailed history from pre-Confederation to 2000 established by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Indian residential schools. It was an “incredible resource,” she said, and “an absolute treasure for us First Nations people.”

As she researched her family, Talaga discovered the fate of Annie, of other family members and also learned about new family members.

“It all went together, believe it or not, and I kept researching and finding more as I went. There wasn't really an ‘okay-all-my-research-is-done-I'm-going-to-start-to-write’ moment. I did it all together. And I think that's probably the journalist in me. I just sort of do it all at the same time,” she said.

What she discovered about her family was “shocking. You see the intergenerational trauma of what you already lived and how deep it runs and where it all comes from. And I would ask Annie questions in the book… I don't know the answers. I could try and surmise what she was thinking, but I didn't know. I know what I would be feeling. Does she feel the same thing?” asked Talaga.

It was hard, she says, discovering all the information that she did. She took long walks with her dog, ran, did a lot of smudging and went to the lodge.

Going through the process, says Talaga, she learned about the strength of the women in her family and the deep connection she has to the land.

“I knew my mom was strong and my grandma, my great grandma, but seeing what they've lived through and the choices they've made in their life to get me where I am…I think that's what I did really firmly discover,” she said.

In the broader story, Talaga offers a reassessment of Canadian history that challenges the Western history books.

The Knowing, she writes, “provides a different way of seeing.”

“The Knowing” is a term Talaga first heard at Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc in 2021 when a suspected 215 unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School were announced. The surviving children from the school told stories of digging graves, of missing friends. “They called this knowledge ‘the Knowing,’” writes Talaga.

The author looks at the role the Hudson’s Bay Company played in colonization. She writes “Unfreedom thus defined the fur trade. It was a form of slavery unique to Canada that spread throughout all the lands the settlers touched. And it shaped the future of Canadian policy for centuries.”

She also presents a less shiny view of suffragette Emily Murphy, who in 2009 was made an honourary senator by the Canadian Senate. As a member of the Famous Five, Murphy may have got voting rights for women, but that did not include Indigenous women. As well, Talaga points out, Murphy was a supporter and believer in eugenics as a means to prevent Indigenous reproduction.

As for the making of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which brought provinces into Confederation, Talaga writes that its completion “further crushed Indigenous Peoples…Besides driving colonization and spreading disease, the train was used to transport stolen children.”

The Indian Act and its “race-based, genocidal policies,” Talaga writes, “works to take who we call ourselves out of our own control, further taking away our language and making us subjects, making us wards of the state, othering us, making us second-class citizens. Never seen as equals.”

In Talaga’s personal story, she lays bare the difficulties she had in tracking down records, because in many cases records weren’t easily accessible, incomplete or the names of her relations were spelled incorrectly.

In fact, said Talaga, her great uncle took his work about as far as he could possibly go. It was her connections as a journalist over the decades and her knowledge of resources and new connections she made as she researched that allowed her to complete the journey.

Talaga is calling for a database that will allow Indigenous people to find their missing relations. She says something could be fashioned after jewishgen.org, a site for Jewish genealogy, and the United States Historical Memorial Museum’s Database of Holocaust Survivor and Victim Names.

“To me there's no reason why our people can't have something like this,” she said.

After The Knowing had been published, Talaga was contacted by the head archivist for the HBC Archives in Manitoba. Initially she was “slightly terrified” that something she had included in her book had been misinterpreted. Instead, when she arrived, they had laid out two “long giant” tables of information about her family, some of which Talaga had not discovered in her own research.

“I knew (my research) was imperfect. I knew that there would always be more and I would find out more when the book is published. The further along technology is improved, the more records we find, I knew that I would find more,” she said.

Talaga won the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing in 2017 for Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death and Hard Truths in a Northern City. The book was the accounting of seven First Nations high school students who died over 10 years in Thunder Bay.

The 2025 Shaughnessy Cohen Prize will be awarded in September.

The Knowing is published by Harper Collins Canada and can be purchased in bookstores or online at amazon.ca.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.