By Deb Steel

Windspeaker.com Writer

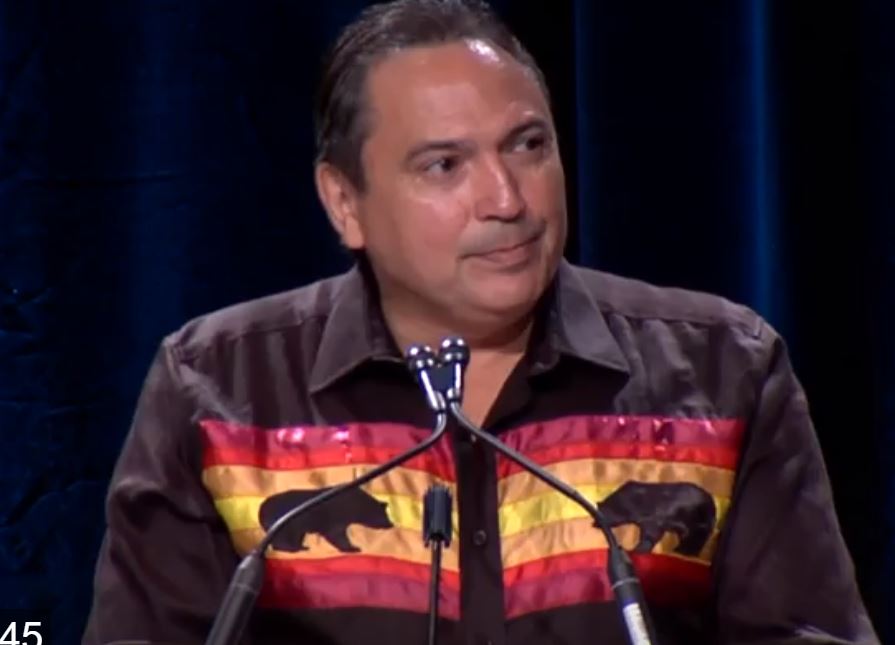

“We’re not saying no,” said Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde.

“We all want to move beyond the Indian Act.”

But saying no is exactly what many First Nations representatives are saying to Canada about its proposed Indigenous recognition of rights legislative framework.

First Nations delegates gathered in Gatineau, Que. Sept. 11 and Sept. 12 to consider the framework, and discuss the affirmation of Indigenous rights, title and jurisdiction.

The Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations Carolyn Bennett was on hand to make the government’s case to promote the legislation and to speak to concerns.

The first day of the two-day event was filled with nay-saying, concern and out-right rejection of the framework. There were strong views expressed at the forum, Treaty 6 Grand Chief Wilton Littlechild would say in his presentation on Day 2.

Bellegarde opened the forum with a statement about Canada’s push to have the legislation ready for December. He insisted that leaders weren’t rejecting the legislative framework, but were jittery about the deadline.

National Chief Perry Bellegarde

“We are slowing things down to do things in a good way,” Bellegarde said. There was “not a good feeling” right now. But with that, the national chief did state the pressure to move forward, reminding the delegates of the upcoming federal election in just over a year’s time.

People did talk about how much better government relations had been since the Trudeau Liberals took over from the Harper Conservatives. A main selling point of the legislation, from the government’s point of view, was that once enacted no future governments could back-track on the obligation of how the Crown could engage on rights implementation. The framework would be Canada’s legislated code of conduct, said Bennett.

It is to be the mechanism to hold Canada to account, moving from the denial of rights approach to implementation of Indigenous rights, said the minister.

Not all delegates were willing to dismiss the legislation wholesale, but there were deep concerns from all quarters with regard to process and content (or lack of content, like the exclusion of Indigenous law). But through the forum participants were able to get down to the nitty-gritty of their disquiet.

From the Beginning:From the time the rights recognition framework was announced Feb. 14, the federal government had a problem, said many. There had been no consultation before the announcement on the need or desire of First Nations for it. Since then the framework had been pushed by government, processed through a government agenda and perspective, and characterized by a lack of transparency, little follow-up with nations on their questions or concerns, and—greatly important—a lack of co-development.

It was, many said, the same flawed approach that had always treated Indigenous nations like bystanders, considerably troubling due to what should have been acknowledged as an extremely complex and detail-oriented process of inclusion. Nations have been responding to government-developed questions and government-produced documents and drafts, instead of holding the pen themselves. It was insulting and misguided, they maintained.

A representative of the Okanagan Nation said the framework process is a step back from the government’s articulated new respect and reconciliation approach.

First Nations should be jointly developing the legislation paragraph by paragraph, he said, understanding the ramifications of it through their own experts, not listening to “lip service” from federal officials who have little of substance to offer in the way of explanation about it.

Bennett said she understood there was cynicism about the initiative, but that seemed an understatement of monumental proportion. First Nations delegates stated their distrust of Canada as a partner, the process, the direction it was headed in and stated fear of the fallout.

The oppressor, said one representative, was now suggesting it had the solution.

“We don’t trust government. We have no reason to. We are skeptical of government and we have every right to be,” said Grand Chief Ed John of the First Nations Summit.

John and Littlechild had been involved with preparing an analysis of the framework for the delegates’ consideration. (Littlechild further suggested that another analysis be undertaken through a Treaty lens). John was clear. The framework draft was found deficient.

Both Grand Chiefs suggested discussions on the legislation carry on, but with care and attention.

History paves a wayOn Day 1, Bellegarde had provided a quick overview of the history Canada would have to confront to build a framework upon.

He spoke about the “illegal and racist” doctrines of Discovery and terra nullius upon which the Crown wrongly assumed its sovereignty and jurisdiction —a legal fiction— and touched on the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

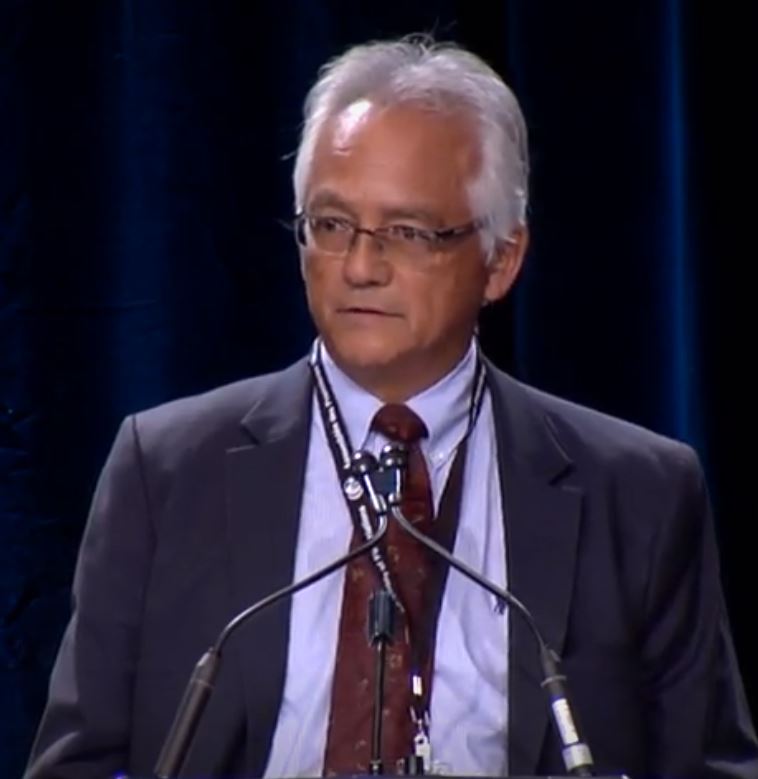

From this proclamation, said lawyer and presenter Dave Nahwegahbow, flowed the concept of “nation to nation relationship”. He said it has become a phrase that often is the rhetoric of modern discourse, but has foundation in the British defeat of the French and, in the years to follow, the assertion by Indigenous nations of their continued sovereignty over their territory. The proclamation prescribed how the Crown would conduct itself with Indigenous peoples, not the other way around, said Nahwegahbow.

Dave Nahwegahbow

Bellegarde briefly mentioned the British North America Act and section 91 (24) in relation to “Indians” and “Lands reserved for the Indians”, (not Indians on lands reserved for Indians), then the 1870 Order in Council and how Indigenous groups should be compensated when their lands are taken up by settlement. There was mention of the Two Row Wampum, and its concept of two canoes, one with Indigenous jurisdiction and the other colonial jurisdiction, going down the river side by side, never to interfere with the governance or the affairs of the other.

Bellegarde talked briefly on the treaty promise to share the land to the depth of a plow and disavowed the idea that Indigenous peoples at the time would understand and agree to “cede, surrender and relinquish” their territories.

He also mentioned the imposed destructive colonial Indian Act and the formation of the provinces, the transfer of lands and resources to them and the off-loaded funding for education, health and social, fiduciary obligations. It was against this backdrop that the framework legislation is being evaluated.

Later that afternoon, Chief Patricia Fairies of Moose Cree Nation would go back to the issue of the provinces. Where are they in this framework, and how will they be engaged?

In her northern Ontario territory, they are being inundated with online staking for mining exploration, she said. With Doug Ford in the premier’s seat and the Conservatives with a healthy majority, there was concern, a concern extended to the other provinces and territories. Delegates believe they are not getting behind Canada’s legislation initiative.

Fairies told Minister Bennett this was a “huge piece missing to your story.”

Grand Chief Littlechild, with many years’ experience in the international arena and on the drafting of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, wanted to know what would happen under the legislation when there is a conflict of views between a province and the Indigenous peoples. Would the minister act as a trustee or take the province’s side?

The province could tell Canada to respect the division of power, said Ed John, also with years of experience on the international scene. “There is a dissonance.”

Not only are the provinces not coming into line, said the leaders, the bureaucracy is not falling into line behind the minister. Delegates acknowledged that the minister was saying many of the right things, but the right action is not following.

“What you say does not go with the actions,” said the chief of Serpent River.

John concurred, saying the bureaucracy is tone deaf to government’s recognition and reconciliation pronouncements. Justice lawyers are status quo. Finance officials are status quo, he said.

The law is with First NationsThe warm blankets of modern Indigenous rights and title recognition successes were layered into the recognition framework discussion, including the 1982 Constitution Sec. 35 with the recognition and affirmation of the inherent rights—a “full box”, said Bellegarde.

The framework legislation was also sitting in the shadows of Supreme Court of Canada decisions from Delgamuukw to Tsilhqot’in and was being put to those tests.

The legislation was being viewed through the lenses of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Organization of American States Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and those standards.

John reminded delegates that from any perspective the assertion of self-determination was already theirs.

“We don’t need Canada’s permission, and nor do we have to ask.”

What they were embroiled in with the recognition legislation was a “power struggle”, he said, and through the two days of discussion they had the solutions for it. John suggested that the AFN set to work to create their own legislation, and talked about two tracks—legislation and policy and practise standards and mandate. He said in many recent legislative initiatives there is a disconnect between the legislative commitment and the practise of it.

It was time to do their homework, John told the chiefs. Speak to the people and come back to the group prepared.

The framework discussion would continue in December at the next AFN Special Assembly.