Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

“For us, for any person, for any nation, for the world to move forward, we need to heal,” said Sol Awashish of Mistissini in the Eeyou Istchee (James Bay) territory in northern Quebec.

“That's a lifetime process. It took me a long time.”

Healing stories have been collected in the first of what’s expected to be four volumes on the residential school experience of the James Bay Cree. As Eeyou Istchee is remote, the Cree in that territory went to residential schools later than many other Indigenous communities.

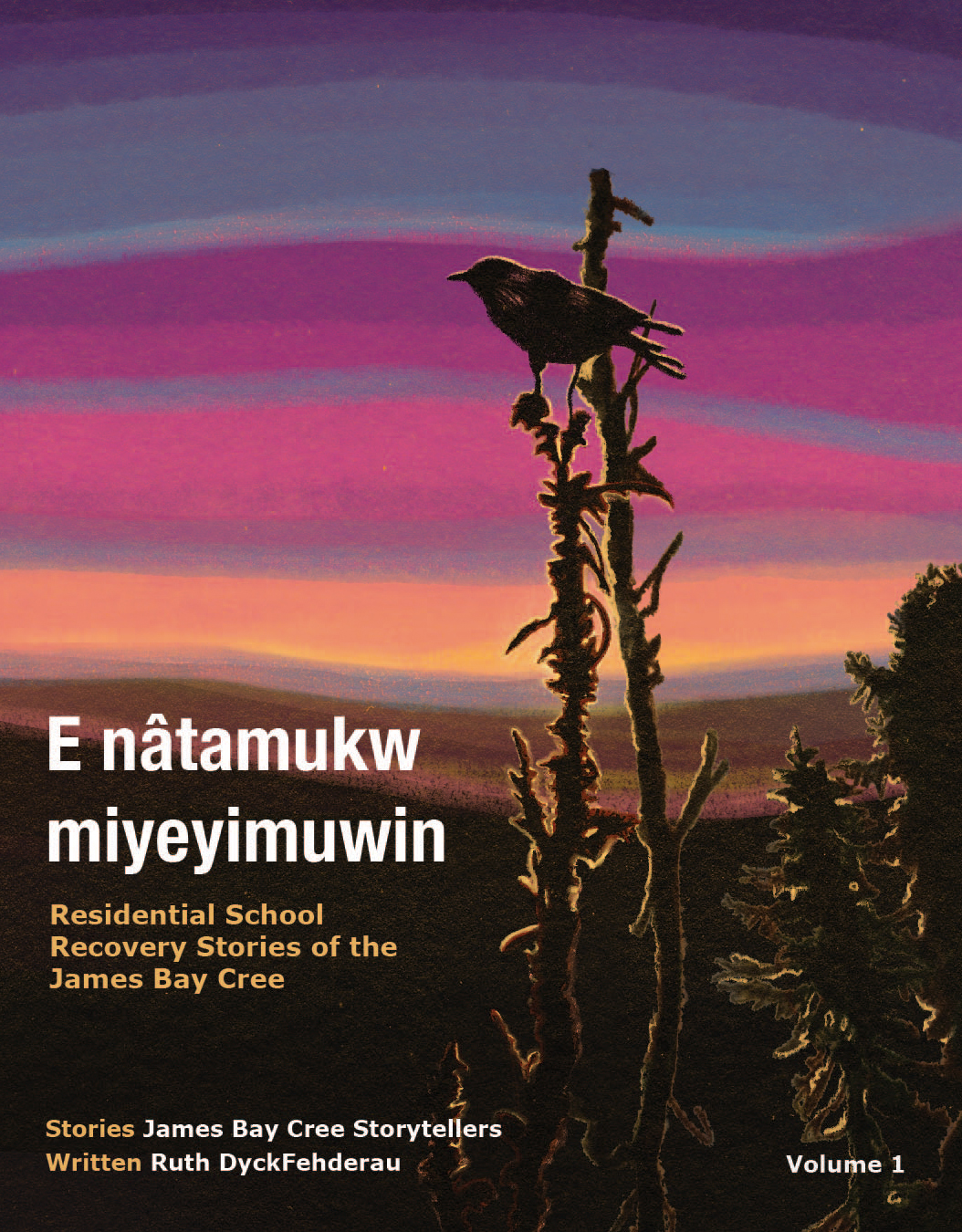

E nâtamukw miyeyimuwin Residential School Recovery Stories of the James Bay Cree contains the accounts of 20 survivors as told to and written by University of Alberta English and Film Studies adjunct professor Ruth DyckFehderau.

Awashish’s story is not in this collection, but he has one. He says at residential school he was made to feel that he deserved to be physically and sexually abused. He was told his culture, his language, his ceremonies were all bad.

“You never really get over it, but you heal from it…First, you accept what happened to you, (that) it's not your fault. But you have to accept what really happened and then you have to learn to forgive the unforgivable…and after that…you take responsibility for your actions and hopefully deal with everything that happened to you and hopefully move on,” said Awashish, who served as Elder advisor to DyckFehderau.

A collection of recovery stories is incredibly important, he says, because people need to know it’s possible to heal.

“One way of (healing) is to talk about it. It took me a long, long time to talk about what happened at residential school. When I used to talk about it either I was drunk, or I would be upset, or I was angry. But now I can talk about it freely. I'm not upset anymore,” said Awashish.

DyckFehderau says the 20 people who met with her saw their stories as “medicine…to help others.”

“They (had) figured out something. Some small corner of the trauma. Or they figured out how to cope with this. There's always something that they have to teach,” she said.

While the majority of storytellers used their real names, seven chose to use pseudonyms. For those people, DyckFehderau says certain details were changed in their stories in order to further protect their identities.

DyckFehderau makes clear that she did not interview the storytellers. She asked only two or three formal questions and then she would “just hang out” with them until they were finished talking. Those visits lasted 45 minutes or over dinner or a couple of days. She revisited the storytellers six months later to ensure the information she collected from them was what they wanted to share. Sometimes details were expanded upon or examples of one incident were exchanged for another incident.

“I worked very hard not to control the direction of the story or the direction of the conversation, and as a person who's been trained by universities in writing, that was something I had to work at,” she said.

DyckFehderau is also a fiction writer, and she used those structural techniques to organize the narratives into short story format.

Unique in the collection is the decision to capitalize the words White, Church, Residential School and Government.

“It’s very clear that they are proper nouns to (the storytellers) because they have so much force,” said DyckFehderau. “That’s how that comes through in (their) speech. And sometimes they will use air quotes.”

One of the challenges she found was in the logistics of returning to the storytellers to get them to sign off on their chapters. Many lived on the land and kept moving, and she had to track them down.

The stories in the collection are difficult to read. The storytellers go beyond the abuse in the residential schools setting. They talk about the lateral violence that was visited on them at home when a family member returned from residential school. They talk about crossing paths with their abuser in their home community. They talk about being let down by the common experience payment or independent assessment program, processes that were established through the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement signed by the federal government that established and funded the residential schools, the churches that operated them and Indigenous representatives.

But they also talk about “going forward,” which is an approximate translation of E nâtamukw miyeyimuwin. Returning to the land and ceremony for many has been a healing experience. Getting counselling has also helped. Confronting an abuser in a controlled manner and receiving an apology have also been important.

“A part of my healing was I met this beautiful woman who accepted me for who I was and helped me heal,” said Awashish. “One of the key things about healing is you need love…You need to be loved and you need to love. What I always consider my own personal greatest accomplishments was to love and be loved.”

DyckFehderau feels honoured to have been chosen to record the stories of the James Bay Cree residential school experience. As she writes in the introduction to the book, “…as one of my supervisors said, ‘Our own (Cree people) have enough to carry.’”

“I actually find this cathartic to know that I am in a position (that) I'm just making sure that these stories are being told,” she said.

DyckFehderau wants non-Indigenous readers to understand that this book is part of Canadian history and that the territory that is now Canada was claimed through “a genocide that was acted upon children and that was instrumental in how we got to have so much land.”

Nothing can change, she adds, until non-Indigenous people understand that genocide was carried out on Indigenous peoples for more than a century through Indian residential schools.

For Indigenous readers, Awashish wants them to know recovery is possible.

“I think we need to teach our youth. We need to teach our children, our grandchildren what we went through and how we recovered from the ordeal,” he said.

He said he would like to see other Indigenous nations telling their stories as well.

E nâtamukw miyeyimuwin Residential School Recovery Stories of the James Bay Cree, Volume1 was published by Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay in March and is distributed by WLU Press. To purchase from Amazon: E nâtamukw miyeyimuwin: Residential School Recovery Stories of the James Bay Cree, Volume 1: DyckFehderau, Ruth, James Bay Cree Storytellers: 9781989796238: Books - Amazon.ca

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.