Windspeaker.com Archives May 1998

By Paul Barnsley

Windspeaker Staff Writer

Politicians get a lot of attention in the press. But the task of making a government function after the politicians have made the decisions is left to the bureaucracy.

In Ottawa, as in all seats of federal power, tens of thousands of people conduct the business of government, each performing a carefully-defined duty with a carefully-defined reporting routine. Each is highly-trained to perform the assigned function. Likewise, provincial and municipal governments are big employers.

But in First Nations where populations range from a couple of hundred people to several thousand, it's different.

There are no budgets, or enabling clauses that would allow the creation of budgets, provided in the federal legislation—the Indian Act—which would pay for an army of administrators and functionaries who could work in support of a First Nation government.

You won't see a legal department or a planning department or a public relations department on a reserve, because there is no established annual budget for such fundamentally-important parts of a legitimate government's job.

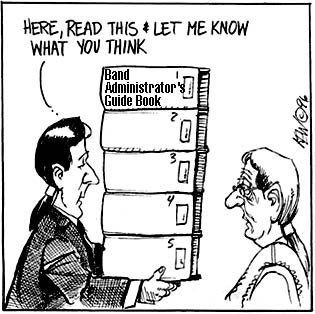

Without money to hire trained people to fulfill such difficult but important functions, the complicated task of overseeing the various programs and departments falls on one person—the band administrator.

The band administrator has to be fully fluent in all provincial and federal legislation which affects funding sources for First Nations. He or she has to keep the band council from getting itself into legal or financial hot water.

His or her job is to know the pitfalls of several very complicated and varied bureaucratic systems and be able to instantly spot a serious flaw in a council's decision. Whether it be federal housing or provincial social services legislation and policy, or any other of an astonishing number of areas of responsibility, the band administrator must be able to advise the elected council so they can make the right decisions.

And, of course, the administrator is the natural scape-goat if things go wrong.

Relying on one person to juggle so much important information and to be responsible for so much can create its own set of problems for a chief and band council. Because the administrator is usually more educated than his or her political masters, (they hire an administrator for his or her expertise because they need it), it's not uncommon for the chief to become little more than a figurehead.

The bureaucrat, the person with the knowledge, gets the power that was given by the voters to the politician. Although more and more Aboriginal people are getting into the field, it's frequently non-Aboriginal people who end up as band administrators.

Bill Wilson, a veteran British Columbia Aboriginal politician and traditional chief, believes it's not good for non-Aboriginal people to be in such powerful positions in First Nations governments, because European and Aboriginal cultures are so foreign to each other. But Wilson also sees it as inevitable because the band council system is a creation of the Indian Act which is a non-Aboriginal creation.

"Indian Affairs sets it up for failure," Wilson said. "There's no support system provided and no money to create your own."

Wilson believes that the answer is to get back to traditional methods of governance. In the traditional systems, he said, positions of political leadership were seen as an awesome responsibility. Leaders, although their positions were (and are) hereditary, had to spend the first 30 years or more of their lives proving to their community that they were fit to lead. That system is far superior to a democratic vote, Wilson said, because the process of choosing a leader does not degenerate into a popularity contest.

In the political system imposed under the Indian Act, (many First Nations people believe) positions of political leadership are seen as positions of power and personal prestige, not necessarily as responsibilities.

They see their chiefs and councillors wielding authority without much attempt at—or taste for—accountability. Indian Affairs Minister Jane Stewart recently told reporters she spent a good part of the month of October 1997 telling chiefs that accountability and transparency is now a must.

She also revealed that many chiefs vehemently protested her department's new accountability procedures. That suggests accountability and transparency have been sadly lacking in First Nation governments up to now, that in many cases the people who protested against the common practices of their band councils had legitimate grievances.

In early April of this year, the Assembly of First Nations seems to have admitted as much by reaching out to the Certified General Accountants Association of Canada for assistance in developing First Nation-specific accounting practices.

Reform Party Indian Affairs critic, Mike Scott, says he has 50 files, each involving a First Nation whose members have complaints about their council's accountability, that he is actively following. He blames the system and the federal government for a lot of the problems.

Westbank Indian Band member Ray Derrickson said that the lack of a funded official Opposition in First Nations leads to abuses. He closely follows developments in his own British Columbia interior community, and he bemoans the lack of financial resources available to make his job easier.

"There's no opposition that's paid for," he said. "How do I go to work on this and put food on the table for my family when there's no money? That lack of funding within the system effectively controls any opposition."

Many people with an intimate knowledge of band politics and operations say the lack of accountability comes as much from fuzzy lines of communication and organization—things that aren't spelled out in any detail in the Indian Act—as it does from any overt act of corruption.

Without well defined rules of behavior and universally understood and accepted methods of communication, mistakes are bound to happen.

Those mistakes can be costly and embarrassing. The stereotype of the Aboriginal person who is too simple, unsophisticated and lacking in the complex skills needed to run a government is fed by the inadequate system, some band councillors say. But when those mistakes in communication occur, the stereotype is also in the minds of the councillors involved and the fear of embarrassment often causes cover-ups. Aboriginal people involved might even buy into the stereotype and believe they aren't as capable as white bureaucrats, Bill Wilson said.

Former Six Nations of the Grand River band councillor Dave Johns was elected to a two-year term in late 1993, despite the fact he is a Mohawk nationalist with no sympathy for the band council system.

He immediately became a thorn in the side of elected Chief Steve Williams and his council. Johns insisted on a level of openness and accountability that was unprecedented in his community.

His close-up look at the system has left him with the impression that the shallowness and unsophisticated nature of the governments created by the Indian Act was no accident.

"I don't think the plan was for us to be around in the 21st century or even the middle of this century," he said. "We were all supposed to be assimilated by then. I've read Indian Affairs documents that talked about the Indian problem in the body politic and what could be done to eliminate it. That Indian Act was supposed to be a temporary thing that would only be around long enough for them to get rid of us."

In any band council or tribal council of any size, Saskatchewan's Meadow Lake Tribal Council or the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation in Ontario have total annual budgets that are close to $50 million, the job of the band administrator is immense. In a typical band administration there are between 10 and 20 departments.

Unlike a municipal government, which is similar in size and in scope of responsibility, the program dollars are budgeted to cover the program only. Also unlike a municipal government, a band council can't raise its own revenue through taxation. That means control of the cash flow is exercised by the funding sources.

That has meant that the administrators who actually do the work may be able to see where it would be wise to deviate from a program, but they don't have the authority to do so.

That can be extremely stressful; if you have to tell people that you can't help them when your job is to help them, you can be sure that each workday will be long and unpleasant.

Burn-out and other long-term disabilities are not uncommon among band council employees, something that drives up the cost of administering the programs and further erodes the amount of money that actually gets used to help the people the program was intended to help.

Once the cash arrives at the First Nation, it makes its way to the department which is responsible for seeing that it is used as the funder intended (In theory, anyway. Councils frequently use money destined for one purpose for another purpose either out of necessity or as a gesture of independence.)

Each department head looks after his or her department and then reports to the band administrator, the one person who must monitor the performance of the department heads and make sure they are keeping their staff members in line and providing an acceptable level of productivity in exchange for their wages.

One would think the administrator would always be a powerful person able to command the respect and obedience of the senior managers—he or she is their boss, after all. But the reality is the politicians are the bosses and their most important consideration is to get re-elected.

They hate saying "no" to anyone because that costs votes. Council jobs and contracts are used as political capital on reserves. Politicians create support by handing out jobs and other favors to those who supported them in the last election.

Just as in one common scenario is that the administrator assumes too much power because he or she has control of all the important information, in another scenario, it's not unusual for a capable administrator to be handcuffed by the politicians.

Indian Affairs Minister Stewart said she is willing to work in partnership with First Nations, but the federal government is only willing to deal with and recognize band councils. Across Canada, the push for a return to traditional government forms may create problems for the federal government even as it attempts to modify the existing band council system.

Recognition of the inherent right to self government and a more respectful approach to First Nations by the federal government may be coming too little, too late to save the Indian Act system.