Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Inuk Elder Naulaq LeDrew now gets a chuckle out of a story that has been passed down through generations to children.

LeDrew recalls she might have been as young as three when she first heard it. The tale goes that someone who is not wearing their hat when the Northern Lights appear will have their head chopped off and it will be kicked around like a soccer ball up in the skies.

“We still tell our young children that so they don’t get frostbitten on their earlobes,” said Naulaq, the narrator of the film Kajanaqtuq, one of 11 short films that will play at this year’s Future of Film Showcase (FOFS).

“Hats are one of the things you most need up north.”

All films in the FOFS festival will be streamed for free and available through CBC Gem from July 9 thru to July 22. Information for all films for the eighth annual FOFS is available at http://www.fofs.ca/

In Kajanaqtuq, which translates into beautiful or breathtaking, LeDrew shares her account of Inuit mythology and historical events of the lands of the north.

LeDrew, 59, grew up in Apex Hill, a suburb of the Nunavat capital of Iqaluit, but has lived in Toronto for the past 30 years. She describes the culture and traditions of her people in the film and details how things have changed in the north, in part, because of government interference.

LeDrew came to understand the significance of the story about hats and the Northern Lights when she was older.

“When I first realized what the story was really meant for, I thought ‘That is a very good idea’,” she said. “It was to give us perspective of what our land can do to us.”

LeDrew is pleased to hear the story is still being told these days.

“We were told to wear our hats because it gets very cold up there,” she said. “And the heat goes from your head, so we used our hats to keep our heat in.”

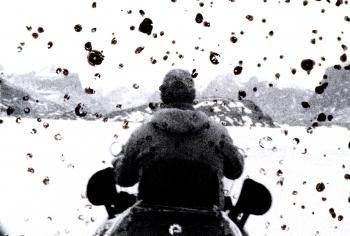

Kajanaqtuq is the debut film for Toronto director Ella Morton. Her background is in still photography. Kajanaqtuq is her first moving image film using experimental analog processes.

She travelled to Nunavut in 2019 to shoot footage on super 8 mm for the film. Through various processes she essentially ‘destroys’ her footage in various interesting ways.

“The purpose of that film destroying is to sometimes show the sublime, the magical, the amazing qualities about the landscape that I’m shooting,” said Morton. “And other times to show the uncertain future that it has. So, it’s both positive and negative ways that I want to show.”

Morton, 35, who also lives in Toronto, is not Indigenous.

“I hope that my work is a platform for the Indigenous stories that Naulaq told,” she said.

Morton said she was not quite sure what direction her film would take when she was gathering footage in Nunavut.

“At the time I didn’t know entirely how it was going to come together as a film,” she said. “But then I found Naulaq through a mutual friend and asked her if she could narrate it and just tell stories about her life in Nunavut.”

LeDrew admits she wasn’t quite sure what was expected of her when Morton initially approached her to be involved.

“I was a little confused because I wasn’t quite sure what she was telling me at the time,” LeDrew said. “When I saw what she was doing I said ‘Ok, we can do this’.”

One of the stories in the film includes LeDrew’s recollection of the 1967 government-ordered slaughter of husky dogs in the north, a colonization tactic.

“Huskies played a huge role in our lives,” LeDrew said. “We used huskies for transportation, we used them for hearing, we used them for sense of smell and we used them to show us where there’s seal holes and to alert us from other predators coming towards us.”

Morton felt it was essential to include this story in the film.

“It’s impossible to ignore the awful parts of the history of what’s happened in this country, to the Inuit and all Indigenous people,” she said. “And so, I think it’s important to include a piece of that, but I do also want to show a variety of stories.”

The picturesque landscape of Nunavut is shown during LeDrew’s narration.

“There’s a lot in the news these days about the trauma (suffered by) Indigenous people, which is necessary and important, but I think it’s also good to show that it’s not all just about trauma,” Morton said.

“There’s tons of interesting things about Inuit culture. I was trying to show every side of what there is up there.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.